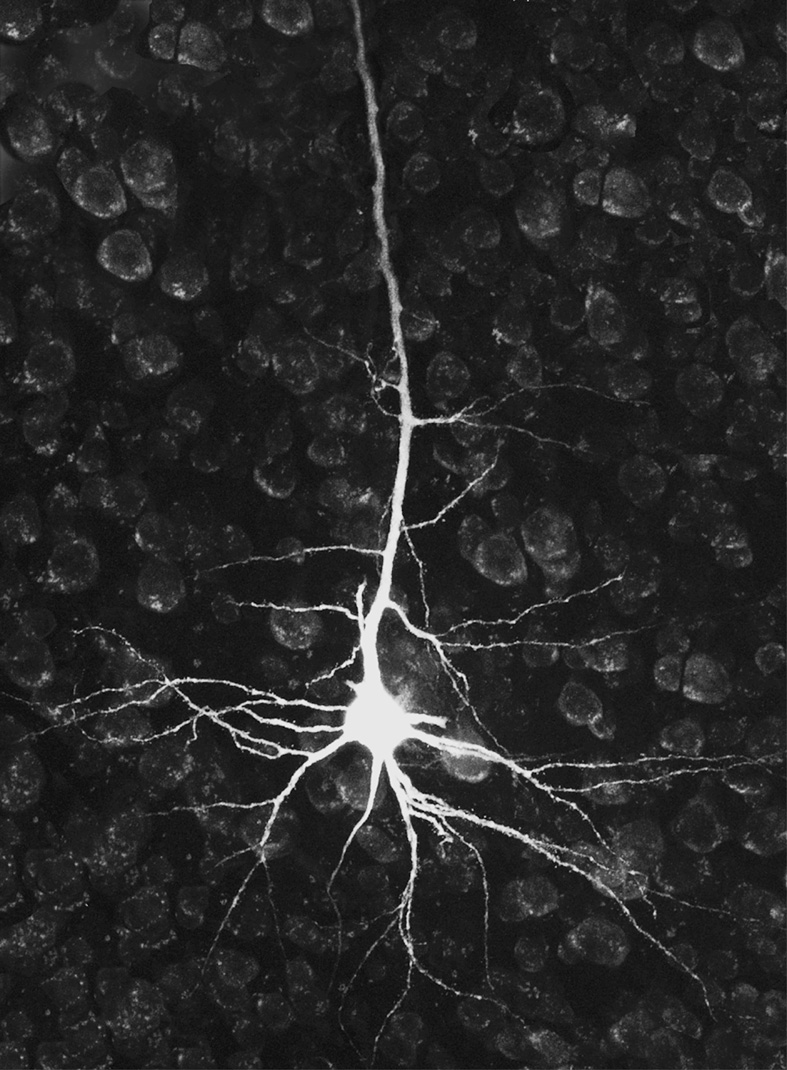

Human neuron

Human neuronAs we’ve mentioned in class and previous notes, some philosophers use names like “physicalism” or “type physicalism” for the view we’re about to discuss. But we’re using those labels in broader senses: either for the very broad view that there are no souls, or for the somewhat narrower view that mental facts supervene on physical facts. The view we’re about to discuss, which we’ll call identity theory, is just one kind of materialist or physicalist view, as we’re using those labels.

Another name sometimes used for this view is “Central State Materialism,” becuse it identifies mental states with states of your brain / central nervous system.

We begin with the observation that there seem to be lawful (that is, systematic and non-coincidental) correlations between our mental states and states of our brain. An example philosophers often use for this is that pain seems to be correlated with having your “C-fibers” stimulated or firing.

C-fibers are a real thing. They have some connection to the perception of pain, but it’s more complicated than most philosophical discussions make out. As I understand it, sometimes you can be in pain when other nerves fire, instead; and neither does every case of C-fiber firing feel like pain. But to keep things simple, let’s pretend that the correlation is as simple as: “you’re in pain if and only if your C-fibers are firing.”

Also, at least in worlds that work like ours, there don’t seem to be any mental changes (in one subject) or differences (between multiple subjects) without a brain change or difference.

What kind of picture or understanding or explanation should we have of these correlations? Kim surveys a range of possibilities (pp. 93-98):

just as a burglar causes footprints, or the dropping temperature causes the lake to freeze, so too the brain state causes the mental state

(so would say a dualist interactionist like Descartes)

the brain state and the mental state have a common cause, like the synchronized dials of different clocks

(so would say Leibniz or Malebranche, in different ways)

the mental state might be an epiphenomenon of the real cause

(this is what the example of the tides is supposed to illustrate; there it turns out that the phases of the moon don’t really cause the tides, but are just an epiphenomenon of their real cause, which is the alignment of sun/moon/earth)

like the temperature and pressure of a gas in a rigid container, the brain state and the mental state might be two aspects of some underlying process that isn’t in itself physical or mental

(so would say Spinoza)

perhaps the brain state and the mental state are identical, as lightning turns out to be identical to electrical discharge

(Kim also discusses another view on the mind/body relation, called “emergentism”, but this doesn’t get an illustrative analogy.)

Smart’s identity theory takes option e.

Sometimes identity theory is summarized by saying the mind is identical to (equals) the brain. But this is misleading. As we said at the start of the semester, materialists don’t need to say that the mind is a genuine entity or substance of any sort, so they don’t have to identify it with the brain (which is a substance). A better summary of identity theory is that every mental state is identical to (equals) some brain state.

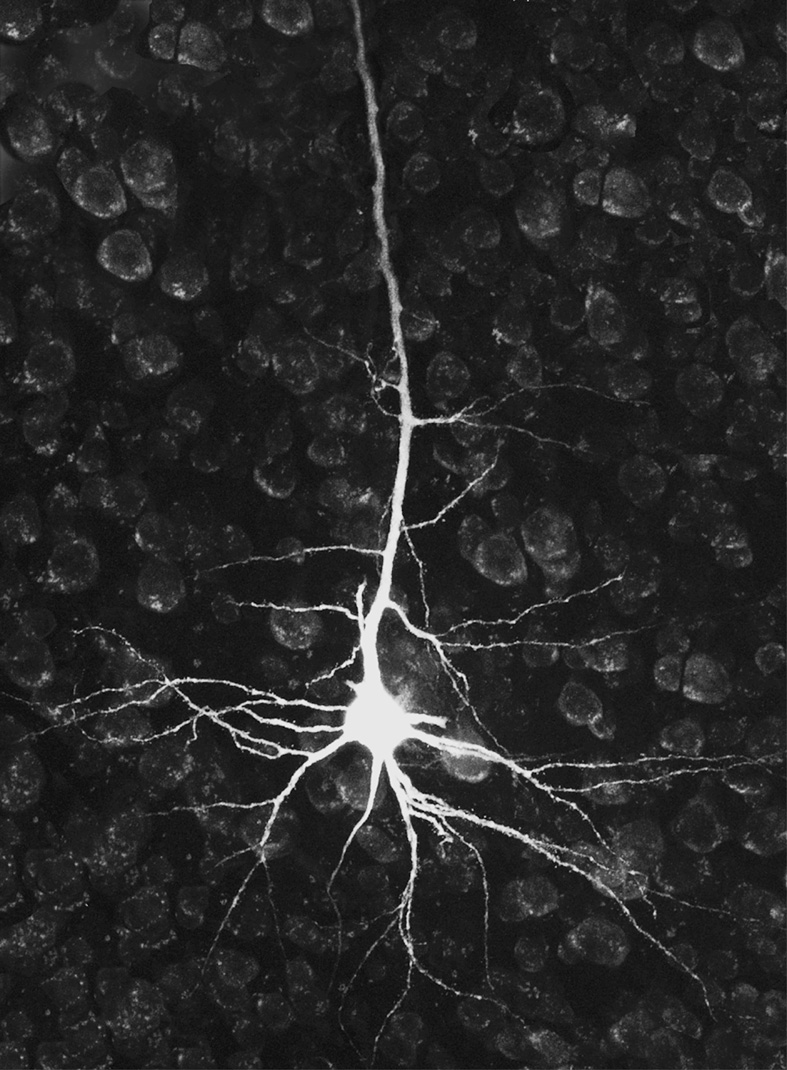

Human neuron

Human neuron

Recall when we were discussing arguments against dualist interactionism, we considered an argument about difficulties the dualist faced accounting for how the mental and the physical “interface” with each other. Kim discusses these difficulties briefly on p. 111.

Kim also discusses the argument that appeals to “Causal Closure”. There are some differences between his presentation of that argument and the one we considered in class. The main difference is that Kim understands “Causal Closure” to include the thesis that there’s no overdetermination of physical effects by both physical and mental causes. Other philosophers don’t understand it that way. As we presented it in class, the thesis of “Causal Closure” just said that if there are mental causes of physical effects, then those effects will be overdetermined because there will be physical causes too. It required a separate step to rule out the possibility that there’s as much overdetermination going on as the dualist would need to say there is. I think our understanding of “Causal Closure” is the more common one. But that’s not important. You should just make sure that you’re tracking how a notion is being used by whichever author you’re reading. Unfortunately, these kinds of terminological differences happen all the time in philosophy.

William of Ockham was an English philosopher in the 1300s. He’s famous for a principle known as Ockham’s (or Occam’s) Razor. In his words (translated from Latin), this says that “entities should not be multiplied without necessity.” This is interpreted and applied in various ways. One common idea is that the simplest explanation — the one with the fewest assumptions and moving parts — is probably and usually the correct one.

Sometimes identity theorists claim it as an advantage of their view that it gives the simplest, most economical, parsimonious and powerful explanation of why mental states are correlated with the brain states they are. For example, Smart writes on p. 61:

[I want to resist the suggestion] that to say “I have a yellowish orange after-image” is to report something irreducibly psychical. [Note: not “physical”] Why do I want to resist this suggestion? Mainly because of Occam’s razor. It seems to me that science is increasingly giving us a viewpoint whereby organisms are able to be seen as physico-chemical mechanisms. It seems that even the behavior of man himself will one day be explicable in mechanistic terms. There does seem to be, so far as science is concerned, nothing in the world but increasingly complex arrangements of physical constituents.

See also the end of Smart’s paper, where he compares the choice between his account and the dualist’s to the choice between orthodox and creationist geology. The orthodox geology is more plausible because it is simpler. The creationist geology postulates too many brute and inexplicable facts. For just the same reasons, Smart thinks, we should prefer his identity theory over the view that our mental states are different from, but perfectly correlated with, our brain processes.

Kim argues against these appeals to Ockham’s Razor on pp. 99-110. I’ll let you evaluate his objections for yourself. I agree with some but not all of what he says. For our class, we don’t need to agree or settle on a definite verdict about who’s right here.

Smart says his view is “not the thesis that, for example, ‘after-image’ or ‘ache’ mean the same as ‘brain process of sort X’… It is that, in so far as ‘after-image’ or ‘ache’ is a report of a process, it is a report of a process that happens to be a brain process. It follows that the thesis does not claim that sensation statements can be translated into statements about brain processes… All it claims is that in so far as a sensation statement is a report of something, that something is in fact a brain process. Sensations are nothing over and above brain processes.” (p. 62, see also his reply to Objection 2)

Earlier in the class, we introduced this contrast between conceptual (or analytic) definitions and scientific (or theoretical or empirical) definitions/identities.

conceptual definitions: these are what you need to know, at least implicitly, to understand the term and think thoughts that we’d express with it. For example, to understand the term “square,” you need to know that squares have four sides. You cannot coherently imagine a square that doesn’t have four sides.

scientific definitions: these are things like “Water is H2O,” “Cows are animals with genetic code GACCTAGCTA,” and so on.

It doesn’t seem to be part of the conceptual definition of water that it be H2O. “Illiterate medieval peasants” can know lots about water, and think things like The carrot field needs more water, without having any idea about hydrogen and oxygen. But arguably what water is, is just H2O. It wouldn’t be metaphysically possible to have water without having H2O. This isn’t something that everyone who has the concept of water can figure out by armchair, a priori reasoning. They’d have to go out and do empirical investigation to learn that it’s true — or they’d have to hear it from someone else, who’s also relying on their own or somebody else’s empirical investigation. Relatedly, it’s not incoherent to think that water might not be H2O. It can be an open epistemic possibility for you that these are different substances. But as it turns out, they’re not. As it turns out, water and H2O are one and the same stuff.

In the same way, what is lightning? Seems like it turns out to be electrical discharge between one cloud and the ground or another cloud. But you can have the concept of lightning without knowing that.

Distinctive features of the scientific identities:

they are knowable only empirically or a posteriori, not by armchair/a priori reasoning that’s available to everyone who has the relevant concepts

relatedly, you can know that water is present, or has some feature, without knowing that H2O is also present / has that feature

you can coherently imagine the scientific identities being false, even if they’re true

Smart thinks these identities have a further feature:

That is, he thinks that in the actual world, mental states and brain states are the same, but it would have been possible for them to be different states. It would have been possible for mental states to be states of a soul (or “ghost stuff”). But as a matter of fact, Smart thinks we have no reason to believe there are souls in our world, nor that pain and so on are states of them.

That was the way that identity theory was usually formulated and defended in the 1950s and 1960s. Unlike many materialists who thought they were giving conceptual analyses or definitions of mental talk, which couldn’t even coherently be imagined to be false, the identity theorists thought that it was just an empirical and contingent truth that mental states were identical to brain states.

Since the 1970s, though, philosophers have mostly thought that if two objects or states are identical to each other, they’d have to be necessarily identical. The only clear exceptions to this are when one of the states describes a role, and the other describes something that happens to fill the role — but it would have been possible for something else to fill the role. For example, “first President of the US” is a role that was actually filled by George Washington, but if history had gone differently, could have been filled by Thomas Jefferson or another statesman. But if we focus not on any role but on the person 👤, that George Washington happens to be identical to, it would not have been possible for him not to be identical to that person.

This is connected to what Kim describes using the technical vocabulary of “rigid” and “nonrigid designators” (pp. 119-120). If you take a philosophy of language class, you’ll learn about these notions. For our purposes, just getting an intuitive grasp of the contrast between talk about roles and talk about the things that fill those roles will be enough.

We’ll revisit and think more about roles and what fill them later in the class. For present purposes, let’s just note that many contemporary philosophers think that if pains really are brain states, then they’d have to necessarily be the same state. So it wouldn’t be possible to have pain without having a brain.

Still, these philosophers would agree with Smart that scientific identities have features 1, 2, and 3. Even if water just is H2O, and lightning just is electrical discharge, these identities can be coherently imagined to be false. Their imaginability-as-false is compatible with them nonetheless being true. Similarly, just because we can coherently imagine being in pain without having our C-fibers fire (or vice versa), is compatible with its in fact being the case that pain just is C-fibers firing.

This is relevant to what Smart labels Objection 7 to his view. Smart agrees with his critic that we can imagine mental states and brain states coming apart: “I say that the dualist’s hypothesis is a perfectly intelligible one” (p. 66). It wouldn’t be like trying to imagine a three-sided square. There’s nothing in the definition, or your understanding of the concept of pain, that would exclude the possibility of you having a pain without having a brain.

But Smart argues, that you can coherently imagine its being false doesn’t imply that it isn’t true. These are supposed to be empirical, scientific identities, that aren’t knowable just on the basis of conceptual understanding and a priori reasoning.

Some of the arguments against Identity Theory are ones we already looked at, when we considered arguments for dualism. For example, the argument that “Medieval peasants knew about their pains, but didn’t know about C-fiber firings or other brain states, so pains can’t be brain states” (Kim p. 115, see Smart’s Objection 1). This relies on applying Leibniz’s Law to a putative property, being such that medieval peasants know about you. As we’ve already discussed, Leibniz’s Law can’t properly/appropriately/legitimately/validly be applied to putative properties like that, that have to do with what people know, believe, have evidence about, or more generally that are sensitive to people’s perspective.

If Smart were defending a conceptual definition of pain in terms of C-fiber firing, then this kind of objection might be a challenge for him. But as we discussed, that’s not the kind of view he’s putting forward.

Another objection Smart considers (his number 4) says that after-images aren’t in physical space, but brain states are. When we discussed this kind of argument earlier, we said that it seems to beg the question in the dualist’s favor. It shouldn’t be granted without argument that the contents of our mind aren’t in physical space. Smart could give the same kind of response. But interestingly, he responds differently. He says he’s not proposing that after-images are identical to brain states. He’s proposing that the experience of having an after-image is identical to a brain state. He’s not proposing any theory of after-images themselves, at all. Perhaps they aren’t really things, and are akin to hikes or dances. Or perhaps they are just an illusion.

We’ll talk more about Smart’s views on after-images and perceptual experience below.

A similar issue would arise with pains. Say you feel a pain “in your leg.” Some people can feel such pains even after their leg is amputated. This raises questions of where the pain really is located. Smart would not be offering a theory of what that pain is (nor of where it is located, if anywhere), but rather a theory of what your experience of feeling such a pain is. He says that experience is identical to a state of your brain.

Another objection Smart considers (his number 6, see also Kim pp. 117-18) says that your knowledge that you’re thinking about elephants right now is direct and “private” in a special way. It’s not based on evidence, observation, or inference. On the other hand, brain processes are public: multiple people can observe them at the same time, and anyone can be wrong about them, even the person whose brain they belong to.

This argument could be understood as another (bad) application of Leibniz’s Law.

But it can be understood in another way as well, which raises more of a challenge for Smart. Namely, if mental states are the kinds of states Smart says they are, then how would it be possible for everyone to have the direct and private kind of access to their own states that they intuitively seem to? And wouldn’t it be possible for a scientist to learn which mental states are identical to which brain states, and then measure your brain and be able to tell you, authoritatively, what mental states you have — even if you might not agree?

Here’s an old Saturday Night Live clip parodying the idea that scientists running medical tests on you could be in a better position than you are to know whether you have pain:

Smart’s Objection 7 we already considered above. This was the argument that since we can imagine pain without a brain, pain states can’t be identical to brain states. Smart and many contempory philosophers agree that the fact that you can imagine these identities to be false doesn’t entail that they are false. They differ in that Smart thinks it would have been metaphysically possible for the identities to be false; whereas the contemporaries think if the identities are true, they’re necessarily true.

The last objection to identity theory that Kim discusses (pp. 121-122) has to do with “variable” or “multiple realizability.” This objection was first powerfully pushed by Putnam (in a 1967 paper we won’t be reading, but is reprinted in the Chalmers collection: as Chapter 11 in the 1st ed, Chapter 12 in the 2nd).

The objection asks us to consider whether for all species (even non-Earthling species, even merely possible species), there will be a single physiological state they’re always in when they have pain? Won’t these creatures have very different physiologies? Couldn’t a creature have pain without having C-fibers? Without even having a brain? Perhaps without even being biological — as opposed to inorganic or mechanical? Especially if we’re thinking about all possible creatures, as we’d have to if we’re a contemporary identity theorist and think our materialist view has to be necessarily and not merely contingently true.

An after-image is what you “see” if you stare directly at a light for a long time and then look away at a blank wall.

Smart’s views on these kinds of experience, and more ordinary sorts of perceptual experiences, are complex and the paper doesn’t have as much sign-posting about this as it should.

Before we get into the details of Smart’s views, let’s consider the range of possible options.

Say you’re having an experience where it looks to you just as if you’re seeing a ripe tomato. Let’s consider three variations of this case. In Case A, it’s a normal case where the tomato really is ripe and you’re seeing it correctly. In Case B, the tomato really is unripe, but it looks red to you because of some glitch in your eyes or your brain. In Case C, there isn’t even a tomato there, you’re just having some kind of lifelike hallucination of a ripe tomato.

Let’s think about Case B for a moment, the case where the tomato is unripe but you undergo an illusion and it looks red to you.

There are three kinds of properties to think about in this case. First, there are various physical properties that the tomato really has. Second, you’re having an experience of the tomato, and there are some properties that your experience really has. Third, there are properties that your experience says that the tomato has, or presents/depicts the tomato as having, but which the tomato might not in fact have. In this case, since the tomato is really unripe, but looks red to you, at least some of these properties that your experience presents the tomato as having are incorrect.

It is controversial which of these properties best corresponds to ordinary language color labels, like “red” and “green.” Philosophers also use special technical vocabulary to name these different properties; but unfortunately there are multiple conventions and not everyone talks the same way.

Here’s how I will talk: I will say that the unripe tomato really has the property of being physically green. (There are different accounts of which physical property that is. Whichever is the best story here, that’s what I’ll call “physically green.”) I will say that the experience in Case B presents the tomato as having some property that it doesn’t really have. And when we want to talk about the properties that the experience itself has, we’ll call them the experience’s own properties.

Now one simple story about how these are all related is:

Some philosophers like that simple story. Others do not. Here are some of the many claims that are disputed about colors and color perception:

Many philosophers agree that in Case A, the tomato really has the properties your experience presents it as having. But some go futher and think that in Case A, your experience also itself has those properties. The tomato and your experience of the tomato are both themselves red, in the same sense. (In cases B and C, your experiences are still red, but no object that you’re looking at is also red.) Usually the philosophers who say this are dualists. If your experience was instead a brain state, presumably it wouldn’t have the same physical colors as the objects you’re looking at.

Some philosophers think that your experience presents the tomato as having properties that really are instead properties of the experience itself. So even in case A, the tomato doesn’t really have the properties it’s presented as having. Instead, it’s the experience that has those properties. (These philosophers might or might not be dualists. Many of these philosophers think that the words “red” and so on name these properties, so they’d say it’s really only our experiences that are red, not objects in the physical world.)

Some philosophers agree with the previous ones that Case A involves a kind of mistake or illusion. But on their view, your experience presents the tomato as having properties that nothing really has, not even the experience itself. (These philosophers disagree whether the English word “red” is a name for physical redness, a property that tomatoes do sometimes really have; or for the illusory properties that our experiences say objects have; or whether “red” is ambiguous between both meanings.)

So there are various different options. We’re not going to sort out now which of these views are correct. I just wanted to give you a sense of how much controversy there is about these issues.

Smart doesn’t make choices about every part of this debate. He does think that when we talk about “red tomatoes” and the like, we’re talking about physical redness. And he does have a favored account of which property physical redness is. He thinks redness is a kind of physical disposition (a “power”) that external objects have (p. 64):

I say that ‘This is red’ means something roughly like ‘A normal percipient [perceiver] would not easily pick this out of a clump of geranium petals though he would pick it out of a clump of lettuce leaves’… I therefore elucidate colors as powers, in Locke’s sense, to evoke certain sorts of discriminatory responses in human beings.

But nothing really turns on Smart favoring that account of physical redness over a different one. What’s important is just that he thinks redness in tomatoes is some physical property.

What Smart spends more time on, at various places in the paper, is exploring what it is for an experience to present something as red or yellow. This is important for him to say something about. Otherwise, a property dualist might agree with Smart that our experiences as of seeing yellow objects or after-images — those mental states — are identical to brain states; but insist that the “yellowness” in them is a matter of some irreducibly mental quality of those brain states. Smart doesn’t want that. He wants everything to be physical. So he has to say how we can account for the presented color in an experience — its looking as if we’re seeing something red or yellow — without bringing in non-physical qualities.

One strategy Smart considers is that when we say things like “I’m in pain” or “That looks yellow,” we’re not really making reports about what properties our experiences have. This is a surprising view, but it has been attractive to many philosophers. Compare: If I say “I’m now writing you a check,” it seems like I’m describing or reporting my present behavior. But if on the other hand I say “I now promise to pay you $100,” it doesn’t seem like that’s what’s happening. At any rate, it doesn’t seem like that’s all that’s happening. It seems like I’m doing more than just describing or reporting my current behavior. (On the other hand, if I say “Yesterday I promised to pay you $100,” there it seems like I am describing or reporting some of my past behavior.) Philosophers capture this by saying that the words “I promise to…” have some non-descriptive or non-reporting function. Sometimes these are called expressivist views.

When Smart talks about Wittgenstein saying that the words “I’m in pain” is a replacement for wincing, instead of reporting some inner state; or when he says that “That flower looks yellow” might be a hesitant or tentative way of saying “That flower is yellow,” these are examples where the language is claimed to not really be making a report about our experiences, but to have some other function instead. In the case of “looks yellow,” the idea would be that this talk involves “going just by looking,” and suppressing any other evidence you have about the flower’s color or reasons not to trust your vision. So it’s a different way of talking about the flower, not a way of describing your inner experiential state.

Smart has some sympathy for these non-reporting views. He’d be happy if they were correct. But he doesn’t think they can really explain all the data, and adequately respond to all the objections their critics have raised against them. So his own view is that talk about “pains” and “looks yellow” and so on do report the subject’s mental state.

We’ve seen that his theory that mental states are brain states isn’t supposed to be a theory about what words like “pain” and “looks yellow” mean, but then Smart still owes us some account of what those words do mean, that is at least compatible with his identity theory.

Smart’s hope is to find some topic-neutral analysis of these words. That is, an account of what they mean that would leave it open whether they are talking about physical states of the brain, or immaterial states of a soul (“ghost stuff”), or something else.

Here is how Smart thinks he can do that, in the case of the notion of “experiencing/having a orangish-yellow after-image.” His analysis of this is (see pp. 64, 66):

Something is going on in you that is like what goes on when you are really looking at a (physically) orangish-yellow object illuminated in good light.

So Smart analyzes such concepts in terms of (i) what the “normal” stimulus is, and (ii) a similarity between your present state and the experience you have when stimulated in that “normal” way.

Comments about this:

Smart’s definition presupposes that we already have some account of what it is for an object to be physically orangish-yellowish. We saw what he thinks about this above (for physical redness). But any account of physical colors could be used here.

Smart’s defintion also presupposes that we already have some account of what it is to be really looking at something. Smart expects us to understand that in physical terms, too: your eyes being opened and focused on the object, and so on.

As we said, although on Smart’s view this definition of “experiencing an orangish-yellow after-image” is supposed to leave it open whether the experiential state is physical or immaterial, Smart thinks that, in our world, these states all turn out to be physical states of the brain. Again: the meaning of sensation-concepts doesn’t require them to be brain states or processes. That identity is instead something it takes scientific investigation (perhaps also appeals to simplicity, parsimony, and so on) to establish.

As well as leaving open whether your experience is physical or immaterial, Smart’s account also leaves open what is the underlying nature of the similarity between your present state and the experience you have when stimulated in the “normal” way. In his view, our world turns out to be one where all orangish-yellow visual experiences are similar because they are brain processes of the same neurological type.

“Functionalist” philosophers we look in upcoming classes will also want to analyze mental concepts in topic-neutral terms. They will try to improve upon Smart’s analyses in three ways: