The word “possible” in English (and related words like “might” and “can” and “must” — philosophers call these modal words) has different uses. If someone comes up to you on the street and says “It’s possible that I was born on the moon,” you’ll most naturally take him to be making some sort of (crazy) claim about what it’s reasonable for him to believe really is the case. You’d be understanding his claim as “For all I know, I was born on the moon.” This is a use of “possible” to express claims about evidence and knowledge. It’s called an epistemic sense of possibility.

But there is another thing the guy might have meant. He might have meant, “Look, I know I was born on the Planet Earth. But things could have gone differently. I could have been born on the moon — if for instance mankind had colonized the moon in the 1800s.” Here he’s using “possible” not in the sense of “for all I know…” but rather in a metaphysical or counterfactual or “alethic” sense. (“Alethic” comes from the Greek word for “truth.”) He’s not talking about what he knows or has evidence for. Instead, he’s talking about what could have happened, if the world or history had been different in certain ways.

Here’s a rule of thumb to help you out. If something of this sort is ever true:

If the world were to be different in such-and-such ways, then P would be the case

then P is what we’ll call metaphysically possible. (Some philosophers say “logically possible.”) If nothing of that sort is true, then P is metaphysically impossible. There’s no way the world could be such that P would be the case.

We’ll be focusing on this second way of using words like “possible”.

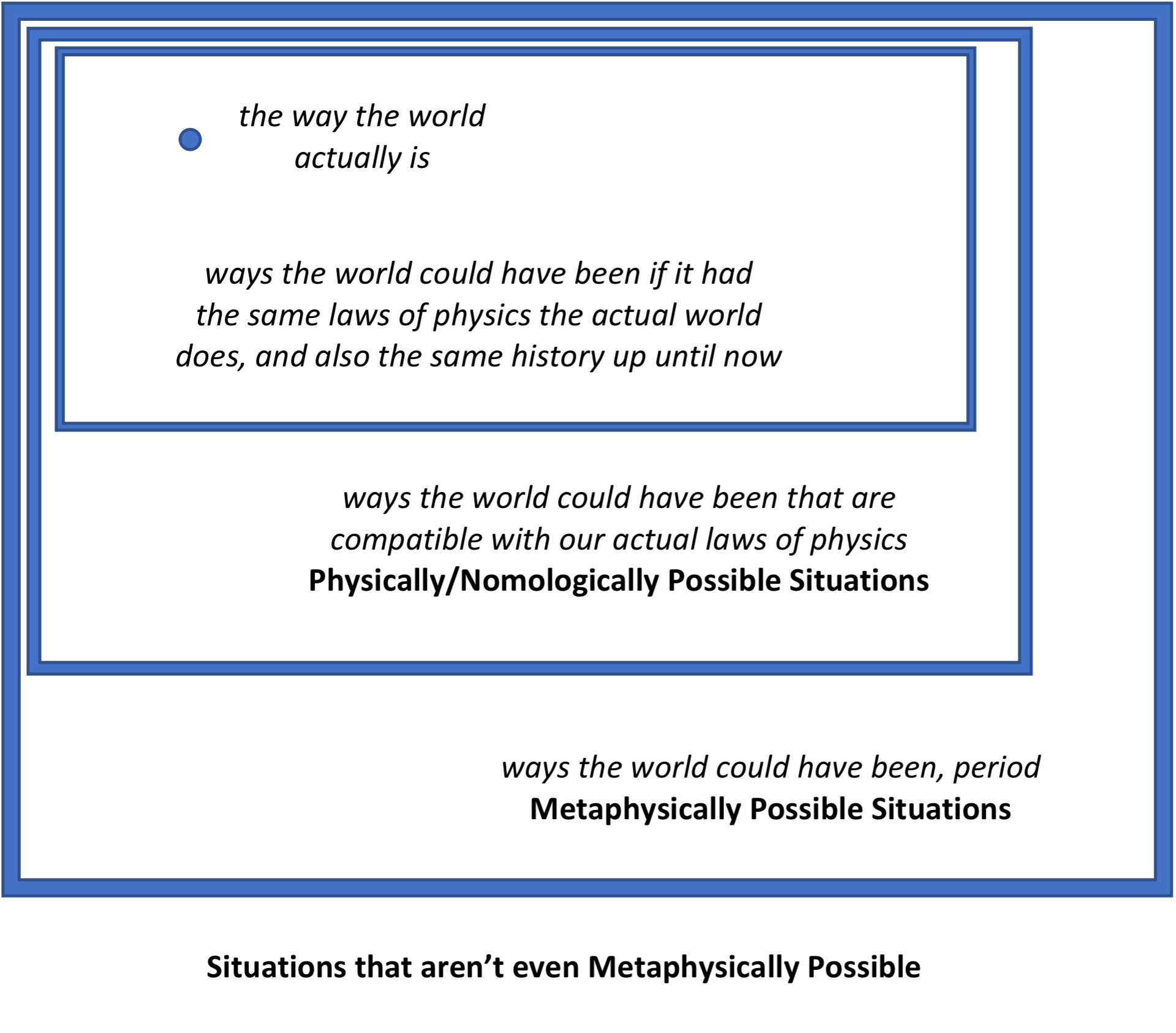

If something is compatible with our laws of physics — if the laws of physics would permit it to happen — then we say that that thing is both metaphysically possible and physically possible. (Or “nomologically possible,” from the Greek word “nomos” for “law.”) If something is guaranteed by the laws of physics, then we say that the thing is physically necessary, and that it would be physically impossible for things to be otherwise.

Many philosophers think things can be possible in a metaphysical sense, even if they’re contrary to our actual laws of physics, and so physically impossible. For example, the charge of an electron might have been larger; or the gravitational constants might have been slightly different. We know that, as things stand, the world is not that way. And if the world had been that way, then perhaps life as we know it would not have come about. But it still seems possible, in a broad sense, for the world to have been that way. Physicists sometimes talk about, and advance hypotheses about, what the world would be like if the laws of physics or the fundamental physical constants had been slightly different.

I mention these different categories to help you get oriented. But what we’ll be focusing on is just the question when things are possible in the broadest, metaphysical sense.

It’s important to be clear about what the bottom category in the diagram, “metaphysically impossible,” means. What it means is that those descriptions are not really ways the world could have been.

Let’s try to come up with some things that would be examples of this.

Would it have been possible for the world to contain 3-sided squares? What would such a world be like? That doesn’t really seem to be a possible way for the world to be, does it?

Nor does it seem to be possible for it to be raining and not raining in the same place at the same time. Nor does it seem to be possible for a person to exist and fail to be one and the same person as himself. There are no possible situations in which things of those sort take place. They all seem to be metaphysically impossible.

Now, so far, the examples we’re coming up with of things that are metaphysically impossible all seem to have something to do with logic or definitions or math. That raises an interesting question:

If something is metaphysically impossible, will that always be because it involves some contradiction or going against some definition?

This is something we’ll need to think carefully about.

Some harder cases:

- would it be possible for you to have been born in Ancient Rome?

- would it be possible for you to have been made of snow?

- would it be possible for you to have never existed?

With the last question we just asked, there are a few questions that differ in subtle ways, but that it’s important to try to keep apart.

One question is, does all the evidence and how things seem to you right now leave open the possibility that you don’t exist? Is it even possible to imagine everything seeming this way to you, but you not existing? Arguably the answer to this question is No. This is what Descartes seems to get at in his Second Meditation when he argues that I cannot reasonably doubt that I exist right now.

If we express this by saying “It’s not possible that I don’t exist now,” we’re using “possible” in the “epistemic” sense mentioned in point 1, above.

A second question is, can you imagine some other time or place (or some other way for the world to be) where you don’t exist? On the face of it, this does seem to be something I can do. I can imagine Ancient Rome, for example, without me being there. Some philosophers argue that this isn’t really achievable after all. They argue that when you try to imagine something, you really have to imagine yourself there observing it. These are interesting issues, but we’re not going to pursue them. If you want to read/think more about them, here is a transcript from lectures by Shelly Kagan, a philosopher at Yale, discussing arguments about this.

A third question is, would it be possible (in the metaphysical or counterfactual sense) for you to have never existed? On the face of it, this also seems to be possible. You might think it’s possible because you can imagine it happening (contra the philosophers mentioned a moment ago). Or you might think that even if you can’t imagine it, still you can understand how it could have happened. If the conditions at the start of the universe had been slightly different, maybe the Earth would never have coalesced where it did and gathered oxygen and so on, and in that case, there would have been no you.

When I asked “Would it be possible for you to have never existed?” I meant to be asking this third question.

Here’s some more jargon.

If it’s metaphysically necessary that a thing have certain properties, then we say that those properties are essential properties of that thing, and that they are part of the thing’s nature or essence. So for instance, oddness is one of the essential properties of the number 3. Some philosophers would argue that being made of wood is one of the essential properties of my table. If they’re right — if it is an essential property of the table — then there would be no possible situation in which the table exists, but it’s made of steel. (There may be possible situations in which some other table exists in the same location, and is made of steel. But if being made of wood is essential to this table, then the steel table would have to be a different table. It couldn’t be one and the same table as this table.) If you agree with those philosophers, you might also incline towards thinking it wouldn’t have been possible for you to have been made of snow.

Those properties which are not essential, we call accidental properties. For instance, being 3 feet tall is only an accidental property of the table (we could saw part of its legs off to make it shorter).

This is a specific technical sense of “accidental,” which of course diverges from the ordinary folk meaning of the phrase. Consider an athlete who eats an excellent careful diet and exercises for hours every day. In the philosopher’s sense, this athlete’s being in good shape is an accidental property — she would still be the same person if she stopped being in good shape. But of course, it’s not a coincidence that she’s in good shape. It’s not an “accident” in the ordinary folk meaning of that phrase.

For philosophers, talk about your “essential” properties is not the same thing as talk about your most important or most valuable properties. It is talk about properties which it is impossible for you to lose. Your wit and charm may be among your important properties. But it’s possible for a person to become un-witty, and un-charming, while still being the same person. So wit and charm are not essential properties.