sam brown, explodingdog

Consider the following two stories.

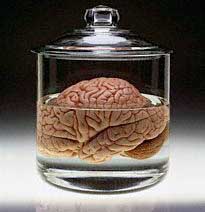

We remove your brain and put it in B’s body. B’s brain gets put in your body. Then we torture one of the two bodies. Which body would you rather have us torture? Most people would prefer us to torture the body their brain originally occupied, rather than the body it now occupies. That is, they believe that they would go where their brain goes.

Now, is it really important to preserve the specific neurons that make up your brain? If we replaced your neurons one by one, you’d still be the same person, wouldn’t you? So it doesn’t seem to be essential to you to keep those particular neurons. Rather, what’s crucial seems to be the information and neural patterns that your brain contains.

Suppose that, instead of moving your brain itself, we instead “scanned” your brain, extracting all that information (and at the same time wiping your brain clean), and then we implanted this information into B’s nervous system. Wouldn’t that be just as good as moving your brain? Let’s suppose we also put the information “scanned” from B’s brain into your original nervous system. Which body would you rather have us torture in that case?

Here too most people are inclined to say “Torture my original body.” They believe that when their information is implanted into B’s nervous system, then they will be inhabiting B’s body. Even if their physical brain stays back in the original body.

This story involves a number of steps.

Suppose we will give you a painful operation with no anesthesia. But we assure you that when the time for the operation comes, you won’t remember that you’re about to get it. Still, this operation seems a frightening prospect.

We tell you that when the time for the operation comes, you won’t only have lost your memory that you’re about to get the operation. You’ll also have forgotten all the things you now believe. You won’t even remember who you are. This doesn’t seem to make the operation any less frightening a prospect.

When the time for the operation comes, you’ll have forgotten all of your current beliefs plus you’ll have a whole new set of fabricated memories. You’ll think you’re someone else. And you won’t know about the upcoming operation. But come it will, and it will still be painful.

This time, all the fabricated memories you’ll have will exactly match the past life of some other person, B. In fact, this is how we’ll implant those memories: we’ll read the patterns out of B’s brain, and copy them into your brain. (We’ll leave B’s brain as it was.) Then comes the painful operation. Does this make the operation any less frightening a prospect?

No, it makes it seem like you’re about to suffer a radical psychological change, and then get a painful operation! If you knew that you were going to suffer this psychological change, and there was nothing you could do about that, but you had the option to pay $1000 ahead of time, to make the operation much less painful, wouldn’t you choose this?

In the last step, we do the same to you that we did in step 4. But we also make B suffer a corresponding psychological change. So B thinks he’s you, and you think you’re B. But you, thinking you’re B, get the painful operation, whereas B, thinking he’s you, goes free. Doesn’t that suck?

Williams is relying on an important intuition in moving to this last step. This is the intuition that identity is an intrinsic matter. Whether two stages A* and A** count as parts of a single person should just depend on what A* and A** are like in themselves, and how they are connected to each other. It should not depend upon what’s going on with other bodies, elsewhere in the universe. (Compare: if we want to know whether two innings are part of a single baseball game, we should only need to look at those innings, and the way they’re connected. We shouldn’t have to look at what’s going on in other ballparks.) So if A and the A-body person can count as being the same person, in step 4, then changes we make to the B-body person in step 5 should not be able to alter that.

When we tell this second story, most people feel at least some pull towards saying that they would stay in the A-body.

The interesting thing is that Story 1 and Story 2 seem to describe the very same situation. There are just differences in how that situation is presented. But when we heard Story 1, we were inclined to say that we went where our information goes, even if our brain stayed behind. Most people would prefer to have the body with their information in it go free, and have the body with their old brain in it get tortured. When they listen to Story 2, though, many people have a different reaction. They’d prefer to let the body with their brain in it go free, and have the other body be tortured. Even if that other body happened to have their brain patterns implanted in it. This illustrates how our intuitions can pull us both ways. When we consider one and the same situation, we can have very different reactions to it, depending on how it was rhetorically presented. Sometimes we think we go where our brains and bodies go. Other times we think we go where the “patterns” or “information” in our brains go.

One response to these puzzles is to say that we just need to make a decision, about which person we’re going to call “the same person” as you. This move is discussed on pp. 41-42 of the Perry dialogue. We’ve already discussed this move, and why it’s unsatisfactory.

A second way of responding to these puzzles is to argue that one kind of evidence for judgments about personal identity is more important than the other kind of evidence. This is what Sam Miller and Dave Cohen attempt to do, in the dialogue. They argue that psychological continuity theories have several advantages over theories of personal identity that count having the same body as more important.

One advantage they claim for psychological continuity theories is that these theories can explain how it is possible to have reasonable beliefs about one’s own identity, without examining anything but one’s own mind. (Normally, one does not bother to check and see if one has the same body, before one judges oneself to be the same person as some earlier person.)

A second advantage they claim for psychological continuity theories is that these theories explain why personal identity is important. They explain why we care about it. For on psychological continuity theories, personal identity consists in the preservation of one’s personality and memories — and these are the sorts of properties that we value very highly. So we care about personal identity, and regard it as important, because it consists in the preservation of properties that we value very highly.

Gretchen allows that Proposal #5 can fairly claim to have these advantages. However, Proposal #5 gives the wrong answer about fission cases. In a fission case, the most sensible thing to say is that the original person is not identical to either of the resulting persons. But Proposal #5 does not permit us to say that.

In order to accommodate fission cases, the psychological continuity theorist has to adopt some more complicated proposal, like Proposal #6, which says that personal identity consists in psychological continuity plus the absence of any competitors. Or perhaps the psychological continuity theorist could instead go with what we earlier called Proposal #9:

Proposal #9 (Brain-Based Psychological Continuity Theory): Stage A* and stage B* are parts of the same person iff they are parts of a chain of psychological continuous person stages, where that psychological continuity is secured by the presence of one and the same brain in every stage. (Dave Cohen introduces Proposal #9 very quickly on p. 47 of the dialogue.)

In Proposal #9, the requirement that all the stages have the same brain guarantees that the later stages have no competitors. Why? Because if B* has the same brain as A*, then any other stage existing at the same time as B* would have to have a different brain. So Proposal #9 is like Proposal #6 in that it makes personal identity a matter of psychological continuity, plus an absence of any competitors. It is just more specific about how the absence of any competitors is to be secured.

Gretchen argues that if the psychological continuity theorist adopts Proposal #6 or Proposal #9, then the supposed advantages that Sam and Dave claimed for psychological continuity theory disappear.

On Proposal #6 and Proposal #9, it is no longer true that one can have reasonable beliefs about one’s own identity, without examining anything but one’s own mind. One also has to check the world, to see whether one has any competitors, or to see whether one still has the same brain one used to have (pp. 47-48).

Likewise, on Proposal #6 and Proposal #9, it is no longer true that personal identity consists just in the preservation of one’s important psychological features. If you step into a teletransporter which “scans” your body and your brain without destroying them, and creates a perfect copy of you on Mars, the copy on Mars will not be identical to you, according to either of these two proposals. He has a competitor (the person who remains on Earth), and he does not have the same brain as you (he has a copy of your brain). Nonetheless, the copy on Mars will have all the important psychological features you have. So on these two proposals, preservation of one’s important psychological features does not suffice for identity. It is not clear, then, that these proposals are in any special position to explain why we regard personal identity as so important (p. 48).

Hence, Gretchen prefers to remain with an account like Proposal #2, which said that personal identity is a matter of having the same body. Or perhaps we should go with an account like the following:

Proposal #3: Stage A* and stage B* are parts of the same person iff they have the same brain. It is not necessary that they also be psychologically continuous. (This proposal is not discussed in the Perry dialogue, but it is very similar to Proposal #2.)

On both Proposal #2 and Proposal #3, one can survive total and irreversible amnesia. On psychological continuity theories, on the other hand, one cannot survive amnesia of that sort, because it destroys psychological continuity. Which view do you think is more plausible?

On Proposals #2, #8 and #9, and #3, one cannot survive teletransportation, even in straightforward cases of teletransportation, where no competitors are created. Why not? Because teletransportation destroys one’s brain and body, and creates a replica of them on Mars. These proposals deny that a person can survive changes which involve coming to have a new brain and a new body.

According to defenders of Proposals #2, #8, #9, and #3, a teletransporter is not a device for transporting a single person great distances. Rather, it’s a device for killing one person and creating a duplicate of that person in his place.

Defenders of Proposal #6 disagree. (So too do defenders of the “closest continuer” theory, which we called earlier called Proposal #7.) These theorists admit that, when the teletransporter produces two copies, the person who went into the teletransporter is not identical to either of the resulting persons (because the two copies compete with each other). But they would say that, so long as the teletransporter only produces one copy on Mars, the person who went into the teletransporter is identical to the person who comes out on Mars.

But the defenders of Proposals #2, #8, #9, and #3 say that the person who went into the teletransporter is never identical to the person who comes out on Mars.