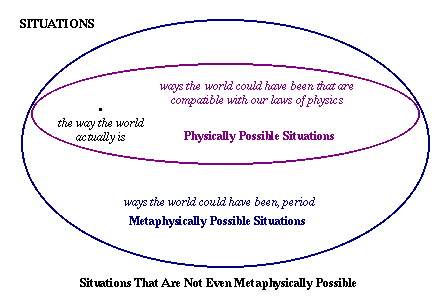

But there is another thing the guy might have meant. He might have meant, "Look, I know I was born on the Planet Earth. But things could have gone differently. I could have been born on the moon--if for instance mankind had colonized the moon in the 1800s." Here he's using "possible" not in the sense of "for all I know..." but rather in a metaphysical sense. He's not talking about what he knows. He's talking about what could have happened, if the world or history had been different in certain ways. We call claims of this latter sort claims about logical or metaphysical possibility.

Here's a rule of thumb to help you out. If something of this sort is ever true:

If the world were to be different in such-and-such ways, then P would be the case...then P is metaphysically possible. If nothing of that sort is true, then P is metaphysically impossible. There's no way the world could be such that P would be the case.

Those properties which are not essential, we call accidental properties. For instance, being 3 feet tall is only an accidental property of the table (we could saw part of its legs off to make it shorter).

- For philosophers, talk about your "essential" properties is not the same thing as talk about your most important or most valuable properties. It is talk about properties which it is impossible for you to lose. Your wit and charm may be among your important properties. But it's possible for a person to become un-witty, and un-charming, while still being the same person. So wit and charm are not essential properties.

Many philosophers think things can be possible in a metaphysical sense, even if they're contrary to our actual laws of physics, and so physically impossible. For example, the charge of an electron might have been larger; or the gravitational constants might have been slightly different. We know that, as things stand, the world is not that way. And if the world had been that way, then perhaps life as we know it would not have come about. But it still seems possible, in a broad sense, for the world to have been that way. Physicists sometimes talk about, and advance hypotheses about, what the world would be like if the laws of physics or the fundamental physical constants had been slightly different.

Let's try to come up with some things that would be examples of this.

Would it have been possible for the world to contain 3-sided squares? What would such a world be like? That doesn't really seem to be a possible way for the world to be, does it?

Nor does it seem to be possible for it to be raining and not raining in the same place at the same time. Nor does it seem to be possible for a person to exist and fail to be one and the same person as himself. There are no possible situations in which things of those sort take place. They all seem to be metaphysically impossible.

Now, so far, the examples we're coming up with of things that are metaphysically impossible all seem to have something to do with logic or definitions or math. That raises an interesting question:

If something is metaphysically impossible, will that always be because it involves some contradiction or going against some definition?

This is something we need to think carefully about.

Let's look more closely at this disagreement. What does the dualist mean when he says that your mental properties are "independent of" your physical properties?

Think of the relation between (i) throwing a ball against a window, and (ii) the window's breaking. Or (iii) striking a match, and (iv) the match catching on fire. There's one event, and it causes the other event to happen. A dualist is perfectly happy to allow that what physically goes on in our bodies causes us to have certain mental states.

Contrast the different set of relations that obtain between (v) being enrolled at NYU, and (vi) being a college student. Being enrolled at NYU doesn't cause you to be a college student; rather, that is just one way of being a college student. There are other ways to be a college student, too; you could be enrolled at some other college. But being a college student isn't some further, optional extra to being enrolled at NYU. Once you're enrolled at NYU, you're then automatically and already a college student. (Assume for the sake of this example that NYU couldn't cease to be a college--it couldn't, for example, turn into a music conservatory or a trade school--and still be NYU.)

The same goes for the relation between some piece of software and the physical states of the computer it's running on. There are certain electrical changes going on in my computer. Also my computer is running a Solitaire game. But the running of Solitaire is nothing over and above those electrical changes. Their taking place doesn't cause my computer to run Solitaire, in the way the baseball caused my window to break. Rather, their taking place is what it is for my computer to be running Solitaire. It would be impossible for my computer to go through those changes and for Solitaire not to be running.

It wouldn't be impossible, on the other hand, for you to throw the ball against the window and the window fail to break. In principle, it's possible that the window might fail to break. It may even be physically possible (for example, if someone installed special dampers on the window). But it would certainly be logically or metaphysically possible for the ball to hit the window, and to bounce away harmlessly. Similarly, it wouldn't be impossible to strike a match and have it fail to light. So this is an important difference.

Let's introduce a new piece of technical vocabulary to help capture this difference.

We say that one set of facts supervenes on another more basic set of facts when the more basic facts somehow "fix" or "determine" that the first set of facts has to be true. That is, when it's metaphysically impossible to have the basic facts settled in a certain way without also having the first set of facts settled, too. So in our example, whether you're a college student supervenes on what institutions you're enrolled at. It's metaphysically impossible to be enrolled at NYU but fail to be a college student. And if you and your friend Teresa are both enrolled at the same institutions, then either you're both college students or neither is.

Similarly, whether my computer is running Solitaire supervenes on what electrical patterns are there inside the computer. If I'm running Solitaire, and your computer has exactly the same electrical patterns, then your computer must also be running Solitaire. It's metaphysically impossible for it to have those patterns but not be running Solitaire.

Here's another example. Some people claim that the beauty or aesthetic value of a painting supervenes on the facts about how the paint is distributed on the canvas. This means that once you've distributed the paint on the canvas in a certain way, you've thereby fixed whether the painting is beautiful or not. Any painting which has its paint distributed in exactly the same way would have to be equally beautiful. It's metaphysically impossible for there to be two paintings that are the same in how their paint is distributed, but different in respect of how beautiful they are.

Here's another example. Some people claim that the beauty or aesthetic value of a painting supervenes on the facts about how the paint is distributed on the canvas. This means that once you've distributed the paint on the canvas in a certain way, you've thereby fixed whether the painting is beautiful or not. Any painting which has its paint distributed in exactly the same way would have to be equally beautiful. It's metaphysically impossible for there to be two paintings that are the same in how their paint is distributed, but different in respect of how beautiful they are.

- I'm not saying that this is the correct view about paintings. Some people argue that forgeries are less beautiful than original paintings--even if they have their paint distributed in exactly the same way. That is a controversial question. But regardless of whether it's correct to say that any two paintings with the same distribution of paint have to be equally beautiful, thinking about that view helps us to understand how the term "supervenience" works. We see that another way to express that view is to say: the beauty of the painting supervenes on how the paint is distributed on the canvas.

Note that when A supervenes on B, it does not automatically follow that B supervenes on A. There might be two paintings of equal beauty which nonetheless have their paint distributed differently on the canvas. That shows that it's sometimes possible to change how the paint is distributed, while leaving the painting just as beautiful as it was before. The claim that the painting's beauty supervenes on the distribution of paint is compatible with that. It only implies that the reverse sort of change is impossible. If the beauty is fixed by the distribution of paint, then you can't change how beautiful the painting is while leaving the distribution of paint exactly the same.

How does all that help us understand the debate between dualists and materialists?

The dualist thinks there is some independent realm of mental substances, and mental facts. But the materialist thinks that the mental facts are "nothing over and above" the physical facts. We can understand what the materialist is saying here in this way: he thinks that all the mental facts about you supervene on all of the physical facts about you. In other words, there could not possibly be someone who is physically just the same as you, without his also being mentally just the same.

The dualist might allow that your physical properties typically cause you to be in given mental states. If I hit you on the head, that will typically cause you to have a headache. But, on the dualist's view, there is nothing metaphysically impossible about there being someone who is just like you physically, but who has different mental properties than you, or perhaps no mental properties at all.

So the materialist thinks that the mental facts supervene on the physical facts: it's metaphysically impossible for two things to be exactly the same, physically, but to differ mentally. The dualist, on the other hand, thinks that it would be metaphysically possible for there to be someone just like you physically but who had a different mental life than you have (or no mental life at all).

If something is metaphysically impossible, will that always be because it involves some contradiction or going against some definition?

Cases of supervenience can supply examples where we have metaphysical impossibilities that are not just the result of some definition.

For instance, perhaps we'd want to say that how beautiful a painting is supervenes on how paint is distributed on its canvas. If so, then it would be metaphysically impossible for two paintings to have the same layout of paint, but differ in how beautiful they are. But we'd be hard-pressed to come up with a definition of beauty in terms of how much, and what colors, of paint are at each spot on the canvas.

Similarly, it seems to be metaphysically impossible for two tables to have the same microphysical structure, but one be such that it would float in water and the other not. We don't need to have a microphysical definition of what it would be to "float in water," to see that that is so.

When philosophers talk about "definitions," they distinguish between:

- conceptual definitions: these are what you need to know, at least implicitly, to understand the term and think thoughts that we'd express with it. For example, to understand the term "square," you need to know that squares have four sides.

- scientific definitions: these are things like "Water is H20," "Cows are animals with genetic code GACCTAGCTA," "Something would float in water just in case...[some microphysical story]..." and so on.

Cases of supervenience show us that there can be cases of metaphysical impossibility that aren't just the result of conceptual definitions. The beauty-facts might supervene on the paint-facts even if we're not able to define "beauty" in terms of how the paint is distributed.

- To begin, we need to distinguish between claims about language and claims about the world.

Suppose there are two women, Beverly and Helen. And suppose I'm madly in love with Beverly, but she doesn't know I exist. Helen on the other hand is in love with me, but I don't like Helen. What I want is to be loved by Beverly. How could I get what I want?

Would getting Helen to change her name to "Beverly" help me get what I want? Of course not. Even if Helen changed her name, she would still be Helen, and Beverly would still be Beverly. It doesn't matter what names we call them. What I want is to be loved by a certain person, Beverly, not just to be loved by somebody or other whose name is "Beverly."

Similarly, a stone would still be a stone, even if there were no people. It would still be a stone even if no one used the word "stone" to talk about it. It would still be a stone, though it would not be called "a stone." It would still be a stone, even if people called it by other words, like "dog."

- "Jim Pryor" is a name for me, the person I actually am. Now, could I fail to be Jim Pryor? Well, there might be possible situations in which I have a different name, and so in which I'm not called "Jim Pryor." There might be possible situations in which other people are called "Jim Pryor." But I'm not interested in those situations. I'm not interested in what people might be called.

Nor am I interested in the question whether I might inhabit a different body.

"Jim Pryor" is a name for a particular person, not a name for some human body. What I want to know is: could there be any possible situations in which I'm not that person? Any situations in which that person, Jim Pryor, the person who is actually called "Jim Pryor," is somebody other than me?

It does not seem like there could be. For there to be such a situation, I would have to be somebody other than the person I actually am. And that is not possible. The person I am can not possibly be identical to something other than himself.

It may be possible for me to live somebody else's life, and to be called by somebody else's name. For instance, perhaps I could have lived the life of Napoleon, and have been called "Emperor Napoleon," instead of "Jim Pryor." But even if that were to occur, and I experienced all the events of Napoleon's life, it would still be me, this person, Jim Pryor, the person who is standing before you right now, experiencing them.

So now we have one result:

It is not possible for me to be somebody other than Jim Pryor, the person I actually am. It is not possible for me to exist without Jim Pryor's existing.

- And yet, in certain circumstances, I would be able to imagine or conceive of myself existing, while disbelieving that I am Jim Pryor, and even while imagining that Jim Pryor does not exist. For instance:

Suppose I get amnesia, and forget my name. I think that Jim Pryor is somebody else. I hear bad things about Jim Pryor and so I decide to kill him. I think, "The world will be such a better place, with me in it but with Jim Pryor no longer existing." Isn't that imagining myself existing without Jim Pryor's existing?

So our second result is:In certain circumstances, I might imagine or conceive of a world in which I exist but Jim Pryor does not.

I can conceive of such a world, but as we've already seen, such a world is not genuinely possible. Hence, the mere fact that I can conceive of something does not guarantee that that thing is genuinely possible.Many philosophers used to think, like Descartes, that if you could conceive of something without contradiction, that shows that it's possible. Some philosophers like Arnauld raised objections to this; but a good many philosophers thought it was true. Nowadays, philosophers realize that you have to be more careful. There is no contradiction in the amnesiac professor's conception of himself existing but Jim Pryor's not existing. At least, there is nothing there that goes against any conceptual definitions he has for "I" or "Jim Pryor." He knows how to use those terms perfectly well, and no amount of pure reasoning or logic will enable him to figure out that they name the same person.

So the fact that you can conceive of something without any conceptual contradiction can at best be a piece of evidence that the thing is possible. It can't be an absolutely certain proof. Some things can be conceived of that are not possible, but rather necessarily false. One only manages to conceive them because one is ignorant in certain ways. They are necessarily false, but one does not know that they are false.

The case of the amnesiac professor is an example of that. The amnesiac professor does not know that he is Jim Pryor. So he does not know that wherever he goes, there Jim Pryor goes. It's nonetheless necessary that wherever he goes, there Jim Pryor goes. What's necessary and what's possible for him depends on which object he is. It does not depend on what people know about him.

- We say that something is knowable a priori when it's possible for one to know it, by reasoning alone. For instance, the fact that 1+1=2 is knowable a priori. We say that something is knowable a posteriori when it's only possible to know it by relying on one's senses, and doing empirical research. For instance, the fact that Queens is located on Long Island is knowable only a posteriori. So too is the fact that it's sunny outside right now, and the fact that Romeo and Juliet was written by a man.

Our example my being the same person as Jim Pryor is another case of something which is knowable only a posteriori. If one does not already know that Jim Pryor and I are the same person, no amount of reasoning alone will enable one to ascertain that this is the case. One would have to do some detective work to find out whether Jim Pryor and I are one person or two.

Yet, as we said, the fact that I am identical to Jim Pryor is metaphysically necessary. So this fact is necessary but knowable only a posteriori. We call it an example of the necessary a posteriori.

- If I can conceive of something without contradiction, then that thing is at least metaphysically possible.

- I can clearly conceive of a world in which I exist but my body does not.

- So it must be possible for me to exist without my body.

If that argument were sound, then so too should this argument be sound:

- If I can conceive of something without contradiction, then that thing is at least metaphysically possible.

- [Suffering from amnesia] I can clearly conceive of a world in which I exist but Jim Pryor does not.

- So it is possible for me to exist without Jim Pryor.

But as we've just seen, the second argument is not sound. Premise (4) is false. So Descartes' argument must not be sound either. The mere fact that he can conceive of himself (or his mind) existing without his body does not show that it is genuinely possible for the one to exist without the other.

Descartes' conclusion may be correct: it may be that his mind and body are really distinct things, which could possibly exist independently. But the mere fact that Descartes can conceive of his mind existing without his body doesn't prove that that is really possible.

Similar remarks apply to our earlier discussion of the inverted spectrum argument. There we saw the dualist arguing that he could conceive of a situation in which two people were exactly the same physically, but they had different experiences. So he thought that showed that it was really possible for two people to be the same physically, but different mentally.

In light of our discussion this week, we can see that there's room here for the materialist to object. He can say: "Hey, whether we are able to imagine or conceive of something is only a fallible guide to whether that thing really is possible. For all the dualist has shown, this might be one of the cases where you can imagine something, but it's really not possible."

Trying to determine which of the things we can conceive of really are possible, and which aren't, is an extremely difficult problem in contemporary debates about the mind/body problem.