Spring 2016, NYU Abu Dhabi

Regress Argument and Sense-Data

There's a lot of complex interactions in the readings for today.

We're going to talk about four arguments, and especially two of them. One of these arguments is the Epistemic Regress argument that Feldman discusses; this also plays a role in Dicker's thinking. The other three arguments have to do with the fact that appearances can conflict or vary, even when or in respects that we think the real objects don't vary. One argument then proceeds to raise an epistemic challenge: since all of the appearances are equally believable, how can we know which one represents the external reality? It seems that all we can immediately know about is how things appear, and then it takes some kind of inferential leap to conclude what the external world is really like. The other two arguments also start with the fact of conflicting appearance, but aren't directly about its epistemic consequences. One of these is traditionally called the Argument from Illusion (Dicker calls it the Argument from Perceptual Relativity). Sometimes philosophers conduct this argument by talking about hallucinations instead of illusions. We'll especially be discussing this argument in connection with Dicker. The last argument appeals to the idea that what appearance we end up having depends in part on the outside objects, in part on the condition of our sense organs (and whether we're wearing colored glasses, etc.), and in part on the kind of light or medium between the outside objects and our sense organs. This argument says that these different factors together cause an appearance in our mind, and that's all we're immediately aware of. That's why appearances can conflict: because some facts about the medium or our senses may vary, even when the object doesn't. It also explains why we have to make an inference to know what real properties the object has that helped cause our appearances, if we're to know anything about those real properties at all.

All of the last three arguments show up in the Russell reading. But we will mostly be focusing on the first, Epistemic Regress argument (in Feldman and Dicker), and on the Argument from Illusion (with traces in Russell, and in Dicker's discussion, though he calls it by a different name).

Epistemic Regress Arguments

Let's begin with Feldman's dicussion of the Epistemic Regress Argument (pp. 49ff).

One way to think about Epistemic Regresses (the one that Feldman pursues) is to talk about (doxastically) justified beliefs. Some such beliefs are justified because of the way that they are based on or inferred from other beliefs. Those earlier beliefs may themselves be based on or inferred from others... How does this end? The possibilities are:

- some of these basing chains go on forever

- some of these basing chains go in circles

- some of these basing chains end in a belief that is immediately justified, that is, justified but not by virtue of being based on some other justified belief

Of course, if there are multiple branching chains, several of these could be true: some of the chains may go on forever, others go in circles, and so on. If we focus our attention on option 3, this subdivides into further possibilities:

3a. the immediately justified belief may be based on an unjustified belief

3b. or it may be based on something other than a belief (perhaps an experience or sensation, or perhaps a "direct apprehension" of something)

3c. or it may be justified without being based on anything

Of course, there is also the skeptical possibility, that none of our beliefs really are justified. But the skeptic might be happy to talk about what structure our beliefs would need to have if they were to be justified.

Foundationalists are philosophers who think that options 1 and 2 aren't really structures that justified beliefs can have; so if our beliefs are to be justified, they have to be justified in some of the ways 3a-3c. (Feldman describes the possibilities a bit differently than I have. He says "either there are justified basic beliefs," and he understands this to include 3b and 3c, or there are three remaining possibilities: what I've called 1, 2, and 3a.)

Coherentists are philosophers who think option 2 is a way that beliefs can be justified; and typically they also deny that any beliefs are immediately justified (options 3a-3c). We'll come back to them in later weeks.

There's another way to think about Epistemic Regresses, too. Here instead of talking about (doxastically) justified beliefs, we instead talk about your justification or evidence or reasons (your prospective/propositional justification). Your justification for believing one thing might come from your justification for believing other things, and so on... How does this end? The possibilities are:

1'. some of these "justification comes from" chains go on forever

2'. some of them go in circles

3'. some justification is immediate, that is, it doesn't come from your justification for any other beliefs

The "goes on forever" option might be more palatable here than in the first regress, since it's easier to imagine an infinite chain of evidence than to imagine an infinite chain of actual beliefs (which it's not clear that any of us have).

Internalism vs Externalism

We've already come across the labels "internalism" and "externalism." Annoyingly, these are defined differently in different discussions. But central ideas in the various ways that internalism gets defined are that "internal duplicates" should be epistemically on a par, and also that justification should come from factors that are "accessible" to you without further fallible empirical investigation (in particular, without relying on any further sensory evidence or contingent assumptions about your external environment).

Coherentists generally hold very strong internalist positions. The epistemologist BonJour, early in his career, is one example. Lehrer was another.

Foundationalists may also be internalists, and traditionally they usually were. Descartes is a paradigm case. Russell, Feldman, and BonJour later in his career were also internalist foundationalists. (Later we'll be reading articles from BonJour while he was still a coherentist.)

One could be a foundationalist and also be an externalist though. The philosopher William Alston (not to be confused with J.L. Austin) was an example. Next class we'll be reading Goldman defending externalism about justification; I don't think anything he says there prevents him from also endorsing foundationalism.

But usually when people talk about foundationalism, especially if they say "Classical" or "Traditional" or "Cartesian" foundationalism (usually these mean the same thing), they have in mind the internalist form of the view. So you can think there are four different camps about justification: Skeptics, Coherentists, Internalist Foundationalists, and Externalists. These don't quite exhaust all of the possibilities, but most epistemologists would identify with one of these camps. Internalist Foundationalism includes the Cartesian, but it can also come in more modest forms.

Questions for the Foundationalist

Feldman raises three questions for the foundationalist and tells us what answers the "Cartesian" foundationalist would give (pp. 52, 55):

Q1. what are the justified basic beliefs about? (Cartesian: your inner mental states, or elementary logic)

Q2. what makes those beliefs justified? (Cartesian: (a) because they are indubitable --- Feldman criticizes this answer on p. 54; (b) or because we are infallible, that is, can't be mistaken about them)

Q3. how do other beliefs get justified by them? (Cartesian: by deduction)

Feldman raises a number of objections to Cartesian foundatonalism. (I'll describe them in a different order than he does.)

One worry he voices is that deduction is too restrictive: it's not possible to deduce everything we intuitively think is justified just from the basic beliefs that the Cartesian posits (pp. 59-60).

Another worry is that beliefs about our inner states are rare; most of us seem to lack these most of the time (pp. 57ff). The Cartesian might argue that we do have these beliefs, they're just non-conscious. Feldman discusses whether the beliefs the Cartesian is positing are really like other less controversial examples of non-conscious beliefs.

But the most interesting discussion concerns the Cartesian foundationalist's answers to Q2. One complaint Feldman makes is that infallibility doesn't automatically translate to justification (pp. 56-7). He also gives two examples purporting to show that we're not infallible about our inner mental states (pp. 55-6): the frying pan example, and the itch had by someone who's been persuaded to accept the false theory that all itches are pains, and so infers that they are in pain.

Armstrong on Infallibility

Armstrong also argues that beliefs we form about our inner mental states aren't infallible. (Armstrong uses the term "incorrigible" and sometimes "indubitable" to mean what we mean by "infallible." Other philosophers sometimes use the terms "incorrigible" and "indubitable" differently.)

One preliminary move Armstrong makes is to distinguish between the claims that some introspective belief, such as that I seem to be seeing something green now, is:

- logically necessary

- infallible (or as he says, "incorrigible")

- a matter about which we have "logically privileged access," that is, even if we're fallible, still our own judgments trump any other evidence

Armstrong says it's obviously not logically necessary that I seem to be seeing something green now; this could well have been false. The tricky question is (b): that is, whether when I judge that things do look that way to me, I could be mistaken. In Section II of his paper, Armstrong argues for the answer Yes. We'll consider these arguments in a moment. In Section III of his paper, Armstrong considers the fallback position that even if we're not infallible, perhaps we still have "logically privileged access". (He cites the philosopher Ayer as defending that view.) Armstrong argues very quickly against this fallback position. (He says, if I might have the mistaken belief and a "brain technician" scanning my brain have the correct belief, why shouldn't it be possible to get evidence that this is so? Why must I always be the better authority than the brain technician?)

It's not essential for you to master this material.

Some of the arguments in Armstrong's Section II make the point that if there is infallibility, we should only allow it about what's going on in one's mind at this very moment. But there are also two arguments (numbered 3. and 4.) aiming to show that we can't even be infallible about that. Both of these arguments are controversial.

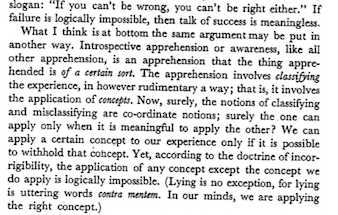

Argument 3. appeals to some principles advanced by Wittgenstein; Armstrong puts it in his own words like this:

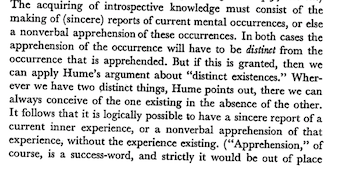

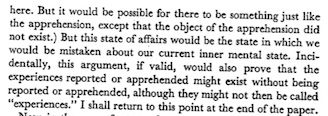

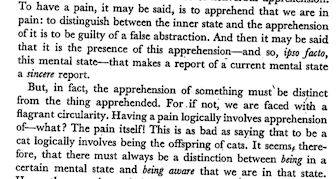

Argument 4. appeals to the idea that an introspective belief would have to involve a report or apprehension of some distinct or separate mental occurrence, and since the apprehension and the occurrence it's about are separate, there can't be a logical connection between them:

Armstrong thinks they have to be distinct or separate, else it wouldn't be possible to say what the apprehension is an apprehension of:

(He thinks it can't be an apprehension of itself.)

As I said, these arguments are controversial. I won't try to evaluate them here.

In Section IV, Armstrong responds to a number of objections. Objections 2. and 5. are interesting.

Objection 2. is: Wouldn't we at least be infallible that it seems to me that I am in some inner mental state (such as pain, or things looking green to me)? Armstrong says sometimes when we say "It seems to me that P," we aren't making a "phenomenological report," but instead just expressing an inclination to judge that P. If the latter, then the question of whether we've correctly described our inner mental state (our phenomenology) doesn't arise, because we haven't even tried to describe it. So there wouldn't be a false report there but neither would there be a true one. On the other hand, if we did make a phenomenological report, Armstrong says why does this report have to be infallible (or as he says, "indubitable")?

Objection 5. is: if our beliefs about our inner mental states aren't infallible or especially privileged, why did philosophers ever think they were? Armstrong offers several suggestions. One of the suggestions (again associated with Wittgenstein) is that sometimes the words that seem to express beliefs about our inner mental states really are playing a different function. For example, "It looks green to me now" might not be expressing a belief about how things visually appear to me, but instead express an inclination to judge that the external object really is green. Or "I am in pain now" might not express a belief about what sensations or discomfort I'm having --- or any belief --- but instead be a funny way of groaning. In those cases, there wouldn't be any false beliefs about one's inner mental state, but that's because there isn't any such belief being expressed at all, not a true one either. On the other hand, when these words do express beliefs about one's inner mental state, Armstrong says why do those beliefs have to be infallible.

The moves Armstrong is making here are controversial. Some philosophers would endorse these moves and others would reject them. We won't try to evaluate them here; I just thought it'd be interesting for you to encounter them.

Armstrong's Section V discusses whether it's possible for there to be experiences that we don't apprehend or have any awareness of. Armstrong thinks yes, that is, the things that we do experience might also exist without our being aware of them, but perhaps in those cases it wouldn't be right anymore to call them "experiences." (Compare: the person who is a teenager might also exist beyond his or her twentieth birthday, but in that case it wouldn't be right anymore to call him or her a "teenager.")

Russell

Russell begins his Chapter 1 by pointing our that the color of the table looks different from different viewpoints, even if we believe the colors really aren't changing:

That passage establishes some facts about varying appearances. These facts motivate Russell to deny that the table has any one real color; instead he thinks that the colors are produced in our mind, partly due to how the table is but also party due to how the spectator is, where she is standing, what light is falling on the table, and so on:

Here I see Russell talking about the fact that the appearances are equally believable, and also giving the diagnosis that all we're immediately aware of are the causal effects that objects have inside our minds. He makes a similar argument about the visible shape of the table:

Though here he doesn't deny that the table has a "real shape." Instead his point is that we don't directly see the real shape, but instead have to infer it from the shapes the table looks to us to have, from where we're standing.

He makes a similar argument about our touch experiences of the table (its felt hardness and so on):

Note the two claims Russell is making here: (a) the real table is not what we immediately experience by sight, touch, and so on; and (b) the real table is not immediately known to us, but must be inferred. Later philosophers argue that (a) and (b) don't automatically go together; you might accept one of these claims without accepting the other. Also, earlier Russell was talking about experiencing the table's properties (its color, shape, hardness); here he is talking about experiencing the table. These might also in principle come apart. (Similarly, immediately knowing the table in the sense of knowing it exists might come apart from immediately knowing what properties it has.)

On p. 12, Russell introduces the term sense-data for the things we immediately know in sensory experience (colors, sounds, hardnesses, and so on). He uses the term "sensation" for our experience of being immediately aware of such things. He takes the arguments of his Chapter 1 to show that our sense-data of the table aren't identical to the "real table" itself, or to its "real shape" and so on.

He summarizes the results of Chapter 1 as:

Note that sense-data is all our senses "immediately tell us" about. This suggests both that they are all we immediately experience, and also that they are all we have immediate knowledge of. Also, Russell says that sense-data are causal effects that external objects have on our minds: they "depend upon the relations between us and the object," and are merely a "sign of some 'reality' behind" them.

Russell uses the expression "matter" to mean objects independent of us, that can continue to exist when we're not perceiving them. There's a stricter sense of "matter" that's opposed to "mind," and implies being incapable of thought or consciousness. Philosophers like Berkeley denied the existence of "matter" in the second, stricter sense, but Russell says they accepted the existence of "matter" in his sense.

Russell's Chapter 2 takes up the question of how we can know that there is a real table, or other kinds of "matter."

On pp. 22-5, he admits that we can't prove (or deduce) the existence of a real table; but it is a simpler and more reasonable hypothesis to believe that there's something there holding the tablecloth up, even though we're not now seeing or feeling it. It's a simpler and more reasonable hypothesis to believe that the cat moved continuously from point A to point B when we weren't looking, than to believe it popped out and back into existence. And so on.

Later philosophers called this style of argument "inference to the best explanation."

In Chapter 3, Russell discusses a number of issues about the nature of real, independently existing objects. One of his claims is that the physical space explored by science is different from the visual space we immediately see, and different also from the tangible space we immediately feel. Also, my visual space is different from yours. Russell thinks there are limits on what we can know about physical space. He thinks we can't know "what it's like in itself," but only about the ways in which it corresponds to our immediately perceived mental spaces.

He also argues that that by "light" we sometimes mean something we directly see, and we sometimes mean some physical "wave-motion," that we don't directly see:

Note that he says the light we immediately see is an effect that waves have upon our senses and mind.

Russell says that all we can know about the physical properties of objects that correspond to our color experiences is when these properties are the same and when they differ. We can only know when they stand in such relations to each other. He says we can't know what these properties are like in themselves:

He rejects the suggestion made at the end of that passage:

Dicker on Perceptual Knowledge

Dicker begins his discussion with the question: "Suppose you perceive x as F. What more is required for you to know that x is F?"

(Notice we're taking up questions of knowledge. Some discussions of perception focus on knowledge and others focus on justification.)

The first proposal Dicker considers is:

Proposal 1. If you perceive x as F, and x really is F, that's enough to enable you to know that x is F.

Dicker argues that this proposal won't work. Suppose you perceive everything as red. Now you look at a wall, that in fact happens to be red. You wouldn't be able to know that it's red, just because it looks red to you. Everything looks red to you. Yet Proposal 1 says you would be able to know that the wall is red. So Proposal 1 is wrong. (See Dicker p. 14.)

Next Dicker considers a more sophisticated proposal:

Proposal 2. If you perceive x as F, and the perceptual conditions happen to be "normal" or favorable (no tricky red lights, your color vision isn't defective, and so on), and x really is F, that's enough to enable you to know that x is F.

This proposal doesn't require you to know that the perceptual conditions are normal. It's enough if they are normal. Here is Dicker motivating (something like) this proposal:

Dicker considers the following objection to Proposal 2:

If this objection is right, then Proposal 2 has to be rejected. The perceptual conditions are in fact normal, and you perceive the water as hot, but you don't thereby acquire knowledge that the water is hot.

Dicker discusses replies to this objection; then he presents a more difficult objection, which he takes to be fatal to Proposal 2. Dicker's objection is this:

Suppose you don't have any independent reason for believing that the perceptual conditions are normal. Then they might be normal, or they might not. You have no way of knowing. If they really are normal, then it would be somewhat "lucky" or "accidental" that this is so. Therefore, Dicker argues, it would again be somewhat "lucky" or "accidental" that this case of perceiving x as F is one where x really is F. And you don't count as knowing that x is F if it's just an accident or matter of luck that you're right about x's being F. (Recall the appeal to the notion of "accidents" in our earlier discussion of the Gettier Problem.) So in cases like these, Dicker thinks, you would not count as knowing that x is F. In order to know that x is F, it's not enough that the perceptual conditions happen to be normal. You also need to know or have evidence that they're normal. (See Dicker pp. 21-22.)

Dicker thinks that it's not enough for you to lack evidence that the perceptual conditions are unfavorable. Neither is it enough for the perceptual conditions to in fact really be favorable. If you're going to know that x is F on the basis of perceiving it as F, you also need to have positive evidence telling you that the perceptual conditions are normal.

Proposal 3. If you perceive x as F, and you know or have reason to believe that the perceptual conditions are currently "normal" or favorable, and x really is F, only then are you in a position to know that x is F.

Here is Dicker motivating this proposal:

At this point a problem naturally arises. How do you find out whether your perceptual conditions are currently normal? (Obviously, you can't just say "By perceiving them to be normal." If you said that, the question would just re-arise: How do you know that the perceptual conditions were normal when you perceived your current perceptual conditions?)

The threat of skepticism looms very large here. If we accept Dicker's Proposal 3, then we can't know anything on the basis of perception unless we have independent knowledge or reasons for believing our perceptual conditions are normal, but how are we supposed to know that, if not by perception?

Dicker on Sense-Data

At this point Dicker introduces the notion of sense-data. He defines these a bit differently than Russell does. For Dicker, these are supposed to be aspects of your experience that you can know about no matter how unfavorable the conditions for external perception are. For instance, when you partially submerge a straight stick in water, it will look bent. In such a situation, you won't be able to know by perception that the stick is bent. (It isn't bent.) But the Sense-Data Theorist says that there is some shape you are aware of which is bent. This is your visual sense-datum of the stick. You can know that the sense-datum or visual appearance of the stick is bent, even if you're uncertain whether or not the stick out there in the world is bent. Similarly, if the wall looks red to you, you may not be sure whether the wall really is red, or whether it's just illuminated by red lights. In such a situation, though, you can know that your sense-datum or visual appearance of the wall is red.

So if we believe in these sense-data, they will be things we can know about in every case of perception, regardless of how favorable the external conditions of perception are, or are known by us to be.

Here is Dicker:

Notice how Dicker is concerned with "avoiding the regress": this should remind you of the Regress Argument Feldman was describing, as a motivation for foundationalism.

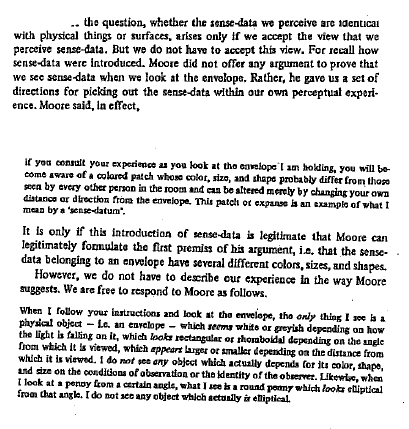

The way Russell introduced sense-data was different. Russell is appealing to different styles of argument. The one we will focus on goes by several names. Sometimes it is called The Argument from Illusion. Dicker calls it The Argument from Perceptual Relativity.

Consider one of the situations where the external world isn't exactly the way it appears to you to be. Some of these cases count as illusions: there really is something there that you're perceiving, you're just misperceiving some of its properties. For example, when the stick is partially submerged in water, it looks bent but in fact it's still straight. If you look at a circular plate tilted on its side, the plate may look elliptical to you. It looks elliptical but in fact it's round. If there's tricky lighting, or you're wearing special contact lenses, the wall looks red to you but in fact it's white. And so on. Other cases count as hallucinations: there isn't anything out there in the external world that you're perceiving, it's just all made up. For instance, Macbeth hallucinates a dagger floating in front of him. You might want to count dreams and being in the Matrix as a kind of massive hallucination.

In cases where the world is the way it appears to you to be, we say that your experiences of the world are "truthful" or veridical.

Some cases of perception are hard to classify. For example, the situation where you're focusing on a distant object and it looks to you like you're holding up two fingers in the foreground, but in fact you're just holding up one finger. Here your experiences are clearly not veridical. There look to be two finger-shaped objects there, but in fact there is only one. But it's not clear whether we should count this as an illusion or a hallucination. (To say it's an illusion is to say that you're perceiving your finger, but just misperceiving it as having some properties that in fact it lacks. What might those properties be? "Being in two places at once"? Perhaps it's better to say that one of the finger-shaped objects is a hallucination. But if so, which one? Are both of them hallucinations? That doesn't seem right; after all, we don't want to deny that you're perceiving your finger. The problem is that you're perceiving it twice. Maybe we need a special category for cases like this.)

In any case, consider some case where your experiences aren't veridical. Some case of illusion, or hallucination, or seeing double. For the sake of example, I'll talk about the stick that appears bent when in fact it's straight.

The Argument from Illusion has two stages. Stage I goes as follows.

The stick appears bent.

So there is some bent shape that you're aware of in your visual field.

But the real stick you're looking at, out there in the physical world, isn't bent. It's straight. (And if you were hallucinating a bent stick, there wouldn't be any real object you're seeing.)

So the bent shape you're aware of can't be identical to the real stick. The bent shape is not a physical object. It's something mental. We can call it your "sense-datum" of the stick.

A Sense-Datum Theorist is someone who believes in these mental objects or sense-data. On his view, these sense-data are what we're really, or most directly, aware of in cases of illusion or hallucination. To figure out what the stick's real physical properties are, we have to extrapolate from the appearances or sense-data we have of it. (For instance, we can look at the stick from a number of different angles, feel it with our hand, and so on, to figure out what its real shape is.)

In Stage I, the Argument from Illusion is talking about cases of illusion and so on. It's trying to argue that in those cases, there are these things, sense-data, that really have the properties that external objects seem to us to have, and that are what we're really or most directly aware of. Stage II of the argument tries to extend this result to cases of veridical perception, as well.

From Stage I, we have:

- In cases of illusion and so on, what we're directly aware of aren't real physical objects, but only the sense-data or appearances those objects produce in us.

The argument continues:

From the inside, cases of veridical perception seem to be just like cases of illusion or hallucination.

So what we're directly aware of in cases of veridical perception must also be sense-data. If what we were directly aware of in the one case were things in our own mind, and in the other case were physical objects in the external world, you'd think we'd notice some difference.

If you go back and read the Russell passages, you should see elements of this argument there. (As I said, there are also elements of different arguments in Russell, too.)

Here are passages where Dicker discusses this way of introducing sense-data, and especially the move from Stage I of the argument to Stage II.

The Sense-Datum Theory was a very popular way of thinking about perception until the 1960s or so. It always had some detractors, but it gives us a very neat, powerful model of how perception works. You look at a stick. The stick causes your brain to be affected in certain ways, and this produces a sense-datum or image of the stick in your mind. What you're aware of is just this sense-datum. It may or may not correspond to the way the stick really is. For instance, the sense-datum may be bent while the stick is really straight. Many philosophers thought that although our sense-data have colors, science shows us that nothing in the external world is really colored. That's just a feature of our own sense-data. And so on.

But the Sense-Datum Theory always had opponents, too; and nowadays, it's out of fashion. There were a number of worries about sense-data that prompted this.

One worry is about where these sense-data are supposed to be located. They seem to have some kinds of spatial properties. For instance, one of my current sense-data is to the right of another one of my sense-data. But sense-data don't seem to be located in physical space. So do I have some special "mental space" where all my sense-data reside? (Recall Russell argued for the answer Yes.)

Another worry is whether we mean the same thing when we say that a sense-datum is "straight" or "round" or "big" or "red" as we do when we say that a stick is straight, or that an apple is round and red, and so on. (Russell used the terms "red" and so on for the properties we immediately see, rather than for the properties of the external obejcts. Other philosophers would talk differently, and call the properties we immediately see "red′" whereas "red" is a property of the external object. But this is just a terminological issue. These philosophers have basically the same picture as Russell. He says it is "gratuitous and unjustified" to think that physical objects have the color properties that we immediately see.)

When I look at an elephant, it appears to be very big to me. When I try to push it, it feels very heavy. Does that mean that my sense-datum really is that big and heavy?

A third kind of worry has to do with the relation between sense-data and our brains. Are the sense-data just part of our brains? (This question is connected to the previous question: how can my sense-datum be as big as an elephant, if it's part of my brain and my brain isn't that big.) Are they produced by our brains? Does believing in sense-data commit you to some kind of mind/brain dualism?

A fourth kind of worry has to do with whether sense-data can have properties other than the ones they appear to us to have. (At first glance, you'd think not. The whole idea of sense-data is that they're supposed to have exactly the properties they appear to have, and no more. But there are problem cases here which make this issue hard to decide. Recall also Feldman's and Armstrong's arguments that we're not infallible about our inner mental states.)

Most importantly for our present purposes is the way that philosophers nowadays view the Argument from Illusion. The general consensus these days is that, if you construe this argument as an attempt to prove the existence of sense-data, the argument is question-begging. Recall the first two steps of the argument:

The stick appears bent.

So there is some bent shape that you're aware of in your visual field.

Here it is simply assumed, without argument, that you are aware of some thing which really does have the property that the stick appears to you to have. This assumption can be rejected. Here is Dicker making that point:

Opponents of the Sense-Datum Theory would say, instead, that you merely seem to be aware of a bent shape. They deny that there is anything which is really bent, anywhere, whether in physical space or in some private "mental space," for you to be aware of. Macbeth merely seems to see a dagger; there is no dagger, not even a mental dagger, which he really does see. In the seeing double case, there aren't really two finger-shaped things anywhere, which you're successfully and correctly perceiving. You merely seem to be aware of two finger-shaped things. In fact, there is only finger-shaped thing. And it's an ordinary physical object. Not some special mental object or sense-datum.

That's what the opponents of the Sense-Datum Theory say. It would only be if you already bought into the existence of sense-data, mental objects which really do possess the properties that external objects seem to us to possess, that you would find the step from (1) to (2) in the Argument from Illusion plausible. It's only people who already believe in sense-data who will accept this move. If you're dubious about sense-data, then you will think this move is illegitimate. If you're dubious about sense-data, you won't think it follows from the fact that something appears F to you that there is any object which really is F.

So the Argument from Illusion relies crucially on a move that would only be accepted by people who already believe in sense-data. That is why, if this argument is supposed to prove the existence of sense-data, it begs the question.

Dicker says at the end of his Chapter 1 that we shouldn't think of the Argument from Illusion (or as he calls it, the Argument from Perceptual Relativity) as trying to prove that there are sense-data. He writes:

[The Argument from Perceptual Relativity] should not be seen...as a straightforward attempt to prove that there are sense-data; for then it is simply question-begging. Rather, it should be viewed as posing the following alternative: either admit that there are no objects whose nature can be perceptually known regardless of the conditions of observation--in which case you will run into a vicious regress when you attempt to specify the conditions under which perception yields knowledge--or admit that there are special objects, sense-data, which are perceived in an epistemologically privileged way, i.e., in such a way that their nature can be known regardless of whether the conditions of observation are normal or abnormal. (p. 27)

Perhaps this is a better way to understand what's driving the fans of the Sense-Data Theory. Dicker thinks that if we don't introduce sense-data, then we won't be able to know anything by perception, since (he thinks) knowing things about the external world by perception requires having independent reason to believe that your perceptual conditions are "normal" or favorable: that is, that your senses are reliable, there's no tricky lighting, and so on. It's totally unclear how we could get that kind of knowledge about our perceptual conditions. At least if we have sense-data, perception will give us knowledge about them. Then we'll have our foot in the door. Maybe we'll be able to build up to knowledge of the external world, using our knowledge of sense-data as a starting point.